![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Basics of Granular Synthesis

Basics of Granular Synthesis

![]() Methods of Grain Organization

Methods of Grain Organization

Sound has been represented to us in a number of different ways by acoustical theorists. Helmholtz postulated that when our ears are presented with a complex audio signal our brain analyses it as a superimposition of sine waves with harmonically related fundamental frequencies. This theory however does not properly allow for the fact that sound changes in time. Gabor (1947) formulated a theory in which he claimed that sound was perceived as a series of short, discrete bursts of energy, each slightly changed in character from the last. He suggested that within a very short time window (10 - 21 microseconds) the ear is capable of registering one event at a specific frequency. This theory has since been mathematically verified by Bastiaans (1980). In fact it is this property of sound that makes it possible for the now familiar digital audio formats to store and reproduce sound as a series of discrete samples.

Prior to

commencing a more detailed explanation of granular synthesis, one cannot help but

to point out that in it's bare essence, granular synthesis does not use anything

that is new or indeed revolutionary to the world of audio signal processing. In

fact, one of the methods employed in granular signal construction (or be it

reconstruction) is based on perhaps the most primitive element of signal manipulation:

scaling of a given value (i.e. the amplitude control). This process is implemented

in any area where the audio signal is being altered - be it the area of mixing desks,

equalisation or the envelope control in a synthesised sound.

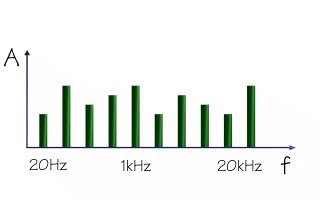

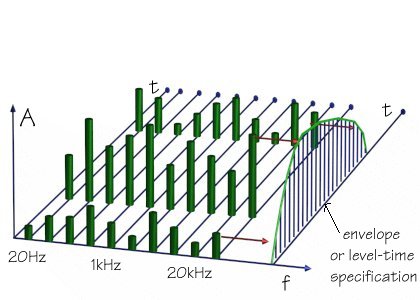

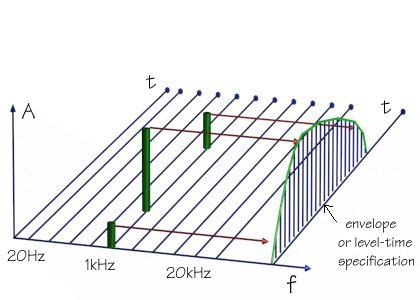

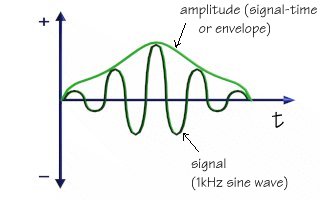

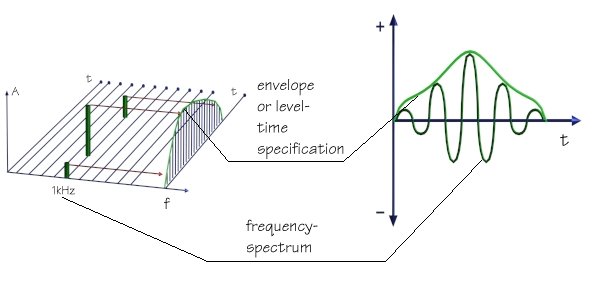

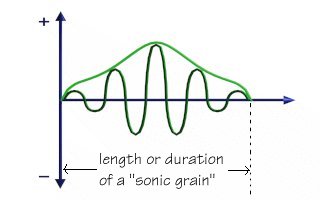

b) frequency-spectrum specification (audio spectrum)

The grain's spectrum is bounded by the amplitude-time specification.

In it's simplest case the frequency-spectrum specification of a sonic grain could be

tought of as a periodic signal (like sine wave oscillator):

To illustrate the above situation in a two dimensional and slightly more conventional

manner the following sketch could be presented:

As one can early see there is a 1kHz frequency which makes up the content of a sonic

grain and there is an overall amplitude envelope which governs the shape of the grain.

So far there have been two methods of signal manipulation established with

regards to the nature of grain's existence (it's envelope and it's spectrum). However,

as it has been mentioned earlier, none of those techniques are particularly new to the

world of signal processing. Yet it is the high level of control and organisation of the

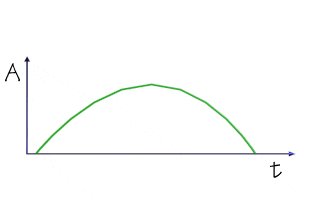

those parameters that makes the difference. Gaussian envelope:

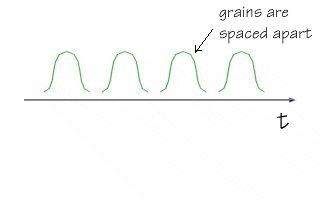

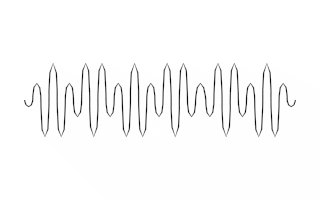

Given that the frequency-spectrum specification is a sine wave, such

arrangement of grains will result in the following audio signal: **) The audio signal:

However, what elevates granular synthesis above any of the primitive signal processing

methods is the extremely high level of control with relation to simple manipulations.

In other words, it is not what is being used to process a signal, but rather it is how

such process is implemented.

Granular synthesis does not invent any new parameters - it simply allows one to control

and manage the existing signal processing techniques on an extremely detailed level.

Essentially, granular synthesis involves the construction of sound from a number of smaller

elements called "sonic grains".

A sonic grain can be seen as a quanta of audio energy - specified and subsequently controlled

in two ways:

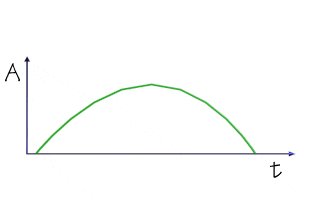

a) level-time specification (i.e. envelope through time)

In order to see how the above diagrams represent essentially the same information

consider the following aid:

By saying "high level of control and organisation" all that is meant here is the precise

description of:

1) the shape of the grain, and

2) grain's duration and

3) grain's spectrum content.

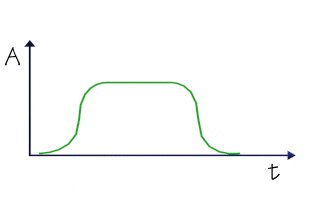

Ad 1) Shape of the grain

Combination of the rectangle shape and Gaussian envelope:

It is quite apparent that different envelopes produce different effects on

granulated sound. A rectangular window for example would constitute a very abrupt

beginning and end of the grain, thus introducing clicks to the audio signal. As a

practical aid consider listening to the example "x1". Those abrupt distortions of

signal could easily be "smoothed" out by using a Gaussian type of grain's envelope

(listen to the example "x2" and compare such to the "x1").

Ad 2) Grain's duration

The next parameter that needs to be precisely specified is the duration of the grain

(i.e. for how long in time each grain continues to exist). To graphically explain such

a concept, the following addition to the above picture could be presented:

The main reason behind such values is the psychoacoustic

nature of human brain at those values. Human perception of frequency, duration and

amplitude tends to reside within practical minimum. As the result, our perception of

the final granulated sound will be open to the effect by those parameters.

In other words human ear will no longer be able to identify each of the grains's shape,

spectrum content, duration, etc. Instead the overall sound created by the combination of

much smaller grains will ber perceived as an output sound.

Ad 3) Grain's spectrum

The simplest form of spectrum content of a grain is a sine wave.

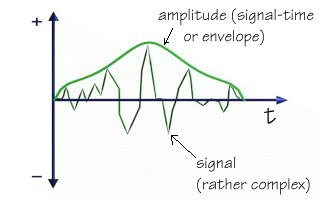

However, one can see that with regard to the "frequency-spectrum" specification of a

"sonic grain" not only sine, square or any other periodic signals could be used. If one

wanted to complicate matters one could find it possible to introduce ANY signal as a

"frequency-spectrum" content of a "sonic grain":

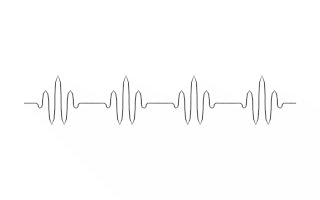

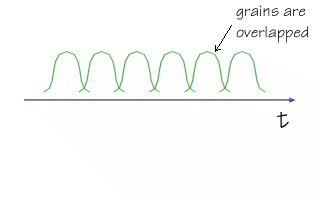

Another important aspect of granular density is: grains do not have to be at a certain

distance from one another, instead they can overlap. As the visual aid consider the

following illustrations:

*)

It soon becomes quite obvious that the more grains overlap the

more their envelopes combine as to reconstruct the original signal. In other words

as density increases the actual effect of granulation of sound becomes less obvious

and the original signal (be it sine wave or a complex sound) is reconstructed.

In file "xc1" the sound starts with grains spaced away

from each other and as the sound progresses the grains get closer and closer and finally

overlap to such degree the sound becomes aurally unchanged from the original (i.e. "xc2").

Screens

One of the first composers to develop a method for composition with grains was Iannis

Xenakis. His method is based on the organization of the grains by means of screen

sequences, which specify the frequency and amplitude parameters of the grains (FG) at

discrete points in time (Dt) with density (DD). Every possible sound may

therefore be cut up into a precise quantity of elements DF DG Dt DD in four dimensions.

The scale of density of grains is logarithmic with its base between 2 and 3, and does

not exist on the screens. When viewing screens as a two dimensional representation, it

is important not to lose sight of the fact that the cloud of grains of sound exist in

the thickness of time Dt and that the grains of sound are only artificially flattened

on the plane (FG). Xenakis placed grains on the individual screens using

a variety of sophisticated Markovian Stochastic methods which he changed with each

composition. The first compositions to use this method were Analogique A, for string

orchestra, and Analogique B, for sinusoidal sounds, both composed in 1958-59. More

recently, a variation on Xenakis' screen abstraction has been implemented into the UPIC

workstation discussed below.

Pitch-Synchronous Granular Synthesis

Pitch-synchronous granular synthesis (PSGS) is an infrequently performed

analysis-synthesis technique designed for the generation of pitched sounds with one or

more formant regions in their spectra. It makes use of a complex system of

parallel minimum-phase finite impulse response generators to resynthesize grains based

on spectrum analysis.

Quasi-Synchronous Granular Synthesis

Quasi-synchronous granular synthesis (QSGS) creates sophisticated sounds by generating

one or more "streams" of grains. When a single stream of grains is synthesized

using QSGS, the interval between the grains is essentially equal. The overall envelope of

the stream forms a periodic function. Thus, the generated signal can be analyzed as a

case of amplitude modulation (AM). This adds a series of sidebands to the

final spectrum. By combining several QSGS streams in parallel it becomes possible to

model the human voice. Barry Truax discovered that the use of QSGS streams at irregular

intervals has a thickening effect on the sound texture. This is the result of a smearing

of the formant structures that occurs when the onset time of each grain is indeterminate.

Asynchronous Granular Synthesis

Asynchronous granular synthesis (AGS) was an early digital implementation of granular

representations of sound. In 1978, Curtis Roads used the MUSIC 5 music

programming language to develop a high-level organization of grains based on the concept

of tendency masks ("Clouds") in the time-frequency plane. The sophisticated

software permitted greater accuracy and control of grains. When performing AGS, the

granular structure of each "Cloud" is determined probabilistically in terms of the

following parameters:

1. Start time and duration of the cloud

2. Grain duration (Variable for the duration of the cloud)

3. Density of grains per second (Also variable)

4. Frequency band of the cloud (Usually high and low limits)

5. Amplitude envelope of the cloud

6. Waveforms within the grains

7. Spatial dispersion of the cloud

Obviously, AGS abandons the use of specific algorithms and streams to determine grain

placement with regard to pitch, amplitude, density and duration. The dynamic nature of

parameter specification in AGS results in extremely organic and complex timbres.